Journalist Report – June 3rd

June 03, 2024, by Jordan Bimm

What life is out there? This question unites astrobiology, the field devoted to searching for extraterrestrial life, and our Martian Biology program at MDRS. Founded in 2019 by Dr. Shannon Rupert, an ecologist and Director Emeritus of MDRS, the Martian Biology program conducts non-sim biodiversity surveys of different field sites reachable from the Hab. We do this to establish a scientific understanding of what’s out there. Not on Mars, but around MDRS. What vegetation, insects, and animals exist in the desert south of the San Rafael Swell? What can an inventory of these forms of life tell us about our Station’s surrounding ecosystems and our planet’s environment?

Now beginning our fourth mission at MDRS, the crew (Crew 298) of Martian Biology IV consists of Shannon Rupert, Paul Sokoloff, a botanist at the Canadian Museum of Nature, Samantha McBeth, a field biologist, Jacopo Razzauti, a PhD candidate in neuroscience at Rockefeller University, Olivia Drayson, a PhD candidate in environmental toxicology at UC Irvine, and me, Jordan Bimm, a space historian and professor of science communication at the University of Chicago. Previous missions in 2019 (Crew 210), 2022 (Crew 243), and 2023 (Crew 282) have focussed on sites located close to the Hab accessible by rovers and have expanded progressively outward using the Crew Car to build a robust and comprehensive regional inventory.

We arrived on Station on Monday June 3, and immediately set to work at a new field site called Hog Spring, 64 kilometers south of MDRS and of special interest to McBeth. McBeth’s goal is to deploy the first of six “Critter Cams,” camouflaged motion-activated digital cameras that automatically record images of wildlife. Adopting the astrobiologist’s mantra of “follow the water” we selected Hog Spring due to its flowing H2O, making it a likely destination for all kinds of local life.

McBeth’s focus this time is on macrovertebrates, mostly larger mammals, although some rodents, amphibians, and reptiles may make an appearance as well and will be welcome additions.

“Realistically, we might see racoons, coyotes, foxes, skunks and weasels,” she says. “Amazing would be images of ringtails, a cousin of the raccoon, mountain lions, or even a bobcat. They’re out there!” The idea is to set up concealed Critter Cams and check back on them in a few days, to see what creatures have passed by and been photographed in the process. For bait, (technical term: “attractant”) McBeth uses a small can of Fancy Feast cat food advertised as “Grilled Tuna and Cheddar Cheese Feast.” “The smellier, the better,” she adds. We poked holes in the side of the can, hid it under a nearby rock, and hoped for the best.

Stay tuned for more updates, including from our Critter Cams, as our week-long mission progresses.

Crew Photos – June 5th

Journalist Report – June 5th

By Jordan Bimm.

Whether you’re on Earth or on Mars, if you’re looking for life, you follow the water. But this year, following the water around MDRS has been harder than ever. After visiting five initial field sites a big early takeaway of this mission is that this year is significantly dryer than any we have seen in 2019, 2022, or 2023. Already we have twice had to adjust our science plans on the fly due to arriving at a site only to find a hoped-for river or creek bone dry. We made tongue-in-cheek comparisons to the ancient river delta at Jezero crater that NASA’s Perseverance rover is investigating. In both cases water once flowed, but not currently. In both cases this absence of water poses a serious challenge for the search for life.

Today, following these setbacks, Shannon Rupert suggested we investigate a new field site she had visited many times in the past, but that our crew had not investigated. Coal Mine Wash is located about a 30 minute drive west of MDRS in the direction of Factory Butte. “If there’s no water at the pool, I’ll really be concerned,” Rupert said. From her description we knew this wasn’t a swimming pool but a prominent pond, a hidden oasis nestled in rock reachable via a short hike through a long-dry riverbed. Stunning rock formations, their rounded edges and oval window-and-arch-like structures, were carved by flowing water millions of years ago and lined the trail, towering over us on either side.

As we hiked in, we paid close attention to any evidence of animal activity. “Scats and tracks,” as Samantha McBeth is fond of putting it. McBeth points out that many types of desert fauna love the plethora of nooks and crannies the rock formations provide. They’re like nature’s condo buildings and perfect for avoiding the sun as well as predators. Walking in we noticed, measured, and cataloged tracks indicating recent pronghorn, mule deer, coyote, red fox, jack rabbit, whiptail lizard, shrew, and ground squirrel activity. Overhead cliff swallows and grey flycatchers flitted past, checking us out. Based on scat patterning, we also identified a likely bat roost in a rock overhang.

As we moved closer to our aqueous destination we noticed an increase in vegetation, which appeared larger and in greater abundance, as well as more bird activity. Strong signals that water lay ahead. Still, we had our doubts, and needed to see the water to believe it.

After twists and turns, and scrambling down a large stone ledge which spanned the miniature canyon, we arrived in the vicinity of “the pool.” Peering over a high ledge and onto the landscape below we let out a whoop of celebration and a sigh of relief. Water. We saw the large circular pond surrounded on all sides by stone walls below us. In the early morning sun the surface appeared bright green and the water level looked low based on visible water rings. We found a narrow pathway along one side which took us down to the soft mud next to the pond where we discovered a menagerie of tracks imprinted.

McBeth sprang into action deploying one of her critter cams, and Jacopo Razzauti began checking the pond for mosquitos and their larvae. Once McBeth had her camera deployed and Razzauti had captured several mosquitos using his aspirator, a tool insect scientists use to literally suck tiny bugs into a collection container, we turned to one final task at the Coal Mine Wash pond. McBeth directed the crew to disperse to different areas around the water source. On her signal we all hit record on our phones’ voice memo app, capturing a 2 minute long soundscape of the site. McBeth plans to use these field recordings of ambient sounds to confirm the presence of birds based on their distinctive calls.

Walking back out, and headed to our next site of the day, Salt Wash, we marveled at the natural beauty of the rock formations surrounding us, and celebrated a badly needed win: water where we thought there would be some.

Crew Photos – June 4th

Crew Photos – June 3rd

Journalist Report – June 4th

June 04, 2024, by Jordan Bimm

The warning sign read: “Water Not For Human Consumption.” But the greenish liquid we were staring at in a cow trough high in the Henry Mountains was more than fit for scientific research. In fact, for neurobiologist Jacopo Razzauti it is a biological goldmine. The water was teeming with life, wriggling with thousands of tiny wormlike critters. “This is larvae heaven,” exclaimed Razzauti, reaching for plastic pipettes and containers.

On the second day of Martian Biology IV, we decided to return to a field site we investigated last year. The Henry Mountains are a prominent range visible from the Hab, appearing as bluish, snow capped peaks in the distance due south. To reach the site we drove roughly 100 km winding up and down the mesa and eventually ascending from the familiar desert to a biologically rich sub-alpine forest. We parked the Crew Car at a site called McMillan Springs Campground, 8,400 feet above sea level.

When we visited this site last year, Razzauti had stumbled upon a cow trough filled with mosquito larvae, his primary object of study as a PhD candidate in neuroscience at Rockefeller University in New York City. Razzauti studies mosquitos to understand this common pest and infamous disease vector responsible for up to 1 million human deaths per year. This year he was anxious to see if the cow trough was still there, and if it again contained a mosquito motherlode.

As soon as Commander Paul Sokoloff parked the Crew Car we were off. Retracting our steps from last year, as if it had only been yesterday, we quickly spotted the trough just below the collection of campsites with their well-used grills and fire rings. As soon as we looked down into the trough our hopes were confirmed, and we quickly got to work.

Razzauti handed me a plastic pipette, a long plastic tube-shaped tool, like a large eye dropper or a small turkey baster. The goal was to collect as many mosquito larvae as possible. Squeezing the blub end of the pipette primes the device for action. Next you try to place the nozzle as close to a wriggling larvae as possible and then release pressure on the blub to instantly suck these proto-pests up into the pipette. Then it’s a simple process to expel the larvae and accompanying water into a small container for transport. The work became a game, and a simple one at that. Within just a few minutes we had captured hundreds of these critters from our impromptu scientific cistern.

“Some made it back to MDRS, but not all of them,” noted Razzauti referencing the portion of the larvae that died on the journey back. At MDRS Razzauti took the larvae container to the Science Dome where he plans to wait for the hardy survivors to develop into pupae, the stage of insect development between larvae and adult. Then he will isolate them, attempt to identify which species of mosquitos are present in our samples, and then track their activity and circadian rhythms. Do they all work on the same clock? Or do they stagger their activity to better share the space? How will these findings compare to last year’s?

Science is often focused on novelty, but today we noticed the value of recursion. You make new discoveries, leverage local knowledge acquired last time, and gain the ability to compare findings from year to year generating valuable insights. It all contributes to the twin goals of making mosquitos less deadly, and furthering our knowledge of non-desert ecosystems reachable from MDRS.

Mission Plan – June 3rd

Martian Biology 4 (MDRS 298) Mission Plan – June 3-10, 2024

This is the fourth non-simulation mission in the Martian Biology program, which seeks to understand the biodiversity of the Mars Desert Research Station (MDRS) operational area, both to better support analog missions and to understand this unique biome. The crew consists of Dr. Shannon Rupert, Dr. Jordan Bimm, Samantha McBeth, Jacopo Razzauti, Olivia Drayson, and Paul Sokoloff.

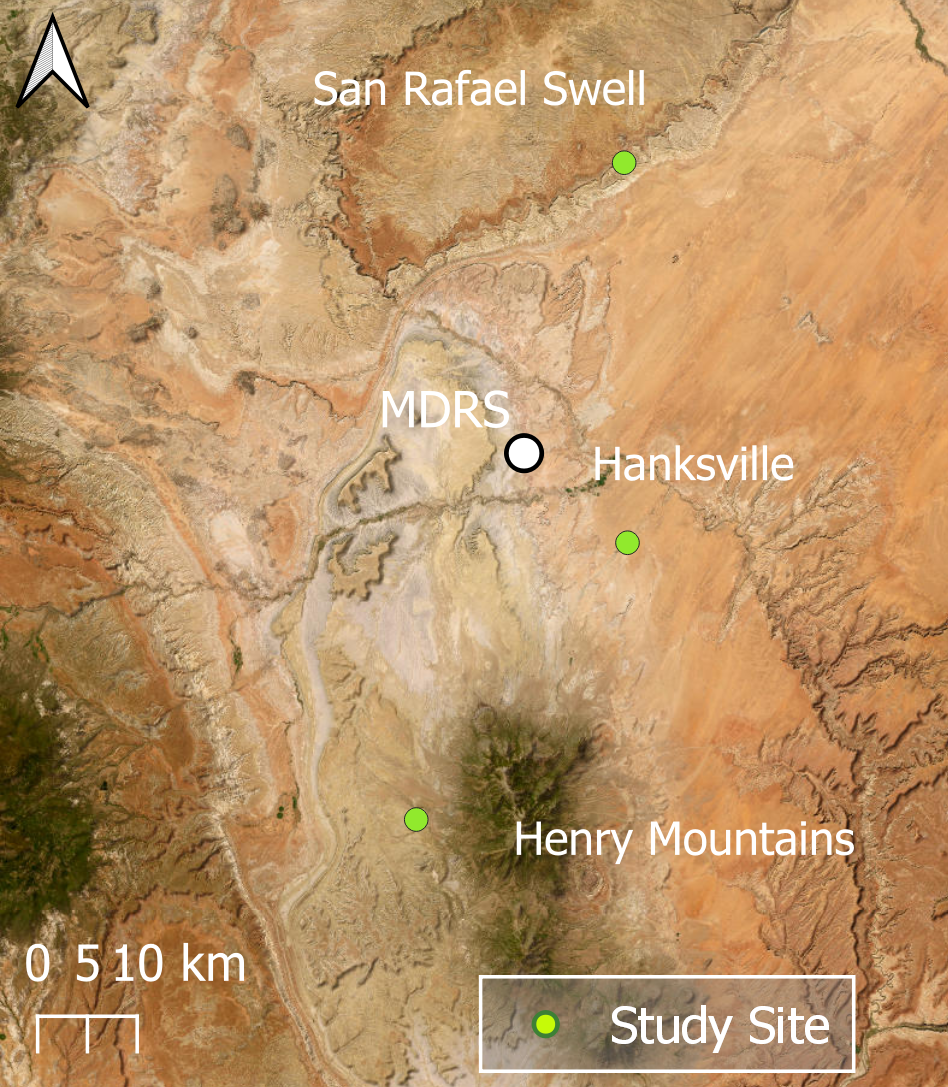

In 2024, we will focus the efforts of our multiple projects at three study sites: Collie Wash (38.32626, -110.67395), the lower slopes of the Henry Mountains (38.07799, -110.91507), and the San Rafael Swell via Temple Mountain Wash (38.66577, -110.67774). Each location would be visited twice – once early in the week to deploy any traps or monitoring devices required, and again at the end of the week to retrieve the samples and/or loggers.

We will continue work on studying the plant and lichen biodiversity of the station through a collections based inventory. We will deploy trail cameras at these locations to better understand the vertebrate diversity at these locations, comparing the data with those available through citizen science platforms (i.e. iNaturalist). We will continue to sample insect diversity with a focus on mosquitos. We will continue to support research into the historical understanding of Martian analogs and astrobiology. We will collect water samples at the study sites to better understand microplastic contamination in the area.

Mission Itinerary:

Monday June 3: Afternoon trip to Collie Wash to collect deposit loggers and traps.

Tuesday, June 4: Science Day on lower slopes of Henry Mountains.

Wednesday, June 5: Science Day at Temple Mountain, San Rafael Swell.

Thursday, June 6: Return to Collie Wash, and collect at waterways along the highway.

Friday, June 7: Return to lower slopes of Henry Mountains.

Saturday, June 8: Return to Temple Mountain, San Rafael Swell.

Sunday, June 9: Flex day.

Monday, June 10: Cleanup at MDRS, mail specimens and gear from Hanksville PO, team leaves MDRS for GJ.

Paul Sokoloff

You must be logged in to post a comment.