Crew 240 Mission Summary

Following a hiatus of one year, after our mission had to be pushed back due to Covid, it has truly been a return to form for Supaero crews at MDRS, as we had the chance to perform two larger-scale rotations in a row this Field Season, for a total of six weeks of combined mission time. This is the Mission Summary of the first of those two crews, and the one that had worked – and waited – the longest before setting foot on Mars.

Our Crew

The selection for Crew 240 took place in late 2019, and the Commander was appointed a few months later, following a first assignment as Crew Journalist as part of Crew 223. We all met each other at that time: five fresh-faced, first year Engineering students, without even a bachelor’s degree; a first year Master’s degree student; and a second year Engineering student, just returned from a first mission at MDRS – all studying at the same place, but with different dreams, desires and objectives for the future. Two years on, it’s clear that this group of seven extra motivated people had grown a lot. We’d seen hard work, doubt, successes, hardships, the hurt of knowing that our mission would have to wait, and the strength to go on and move forward anyway. During those two long years of preparing the mission, we had the chance to acquire knowledge and experience, either in our studies, or in our work in a professional setting. Clearly, this time spent on growth has had a huge impact on the way we approached our mission at MDRS.

Yes, I did mention the number seven on that previous paragraph: that’s how many we used to be throughout all the preparation. Raphaël, the seventh crew member, was set to be our GreenHab Officer, and was responsible for the atmospheric experiments we run with French research centre CNRS, amongst other large parts of our work. We had to go on to MDRS without him due to visa issuance problems, and we miss him for many, many reasons, either it be for his hard tireless work and thorough knowledge of his subjects of focus, or simply his never-ending positivity and good spirits. His absence is felt throughout the Hab all the time, and while he can’t technically be considered a member of this crew, all the work he’s put forward for this mission makes him, in our eyes, just as much of a member of our group.

Our Work

Supaero crews benefit from the wealth of experience and prior knowledge gathered during all the rotations our older students or alumni have participated in, and it’s clear that with this experience, Crew 240 has managed to put together a set of scientific content that far exceeds what had been performed in any prior mission by our crews. A strong desire to push towards the most relevant content, that makes the best use of the specificities of the station, and the region around MDRS, has led to a number of brand-new experiments and continued advances on the experiments we had already brought on. This will be an outline of all the work that was performed over these past three weeks.

Human Factors Research

This year has seen an increase on our attempts to research the ways a stay at MDRS influences us physiologically as well as psychologically.

On the technical performance side, one of our longest-running experiments, TELEOP, once again arrived at MDRS under the helm of Crew Biologist Marion, taking advantage of the longer mission time. Developed in-house at the SacLab Laboratory at Supaéro, this experiment was part of the testing regiment of analogue astronauts for the Sirius mission in Russia, and at MDRS we similarly performed regular tests of simulated rover driving on the Moon, testing fatigue in different physical positions to get Earth-level understanding of how weightlessness can influence performance.

In the meantime, an experiment from the University of Bourgogne offered daily questionnaires to assess a large array of psychological reactions to our living situation, and an experiment from the University of Lorraine combined questionnaires with long, extensive sessions on a piece of software designed to assess attentiveness through numerous tests.

These experiments were performed on time, efficiently and in accordance with the protocols given to us by the researchers responsible for these experiments, under the supervision of Crew Engineer François. While many of them were tiring – by design – the crewmembers took it to heart to put in their best efforts so that our scientific partners gather relevant data.

On the topic of physiology, we have continued to study sleep. After Crews 206, 222 and 223 used Dreem headbands to show the relevance of consumer-level hardware applied for scientific data, we have followed on this work by using Fitbit wrist bands to obtain biometric data across the mission, with the goal to study sleep, performance during sports session and EVA, as well as nutrition from before the mission all the way to the post-mission. This, combined with frequent questionnaires on sleep quality and emotional levels, should help us better understand the physiological and psychological effects of a mission like this one.

Lastly, space medicine company SpaceMedex has entrusted us with another consumer-ready biometrics tool, HexoSkin, a skin-tight shirt that measures data during exercise. This helps us gather extra data from our EVAs, data that not only gives us more precise values for the amount of exercise performed, but can also be used for further analysis of our experiment based on performance on EVA. Both the data of the Fitbit wristbands and the HexoSkin have been collected by Crew Scientist Marion, and will be further analysed after the full duration of the experiment.

Atmospheric and EVA Experiments

While most of our time is spent within the confines of the MDRS campus, a lot of the science we perform takes great advantage of the geographical position and geology of MDRS. In the past, our EVAs were focused on maintaining the experiments we stationed outside; this year, additional ideas have given even more solid purpose to our extravehicular activities, and have led to valuable data being collected on both the human side, and also about the area around MDRS.

Like previous years, French research centre CNRS has offered several instruments for field testing, in the Mars-like terrain of MDRS that they believe can bring valuable results and data. Amongst the tried-and-true experiments, LOAC, a LASER-based aerosol particles counter has had another successful run at MDRS. While MegaARES, the Earth-ready cousin of an instrument launched on the Schiaparelli mission to study electric fields on Mars, has unfortunately suffered from technical issues and was eventually not set up, another newcomer, the Field Mill, designed for the same purpose, recovered its first data from the desert during this mission. To complete the set, the PurpleAir air quality instrument was tested for the first time by our crew at MDRS.

One of the high points of our time spent outside on EVA was based on a partnership with drone company Parrot, who donated consumer drones capable of performing 3D mapping tasks. While the usual maps available to us at MDRS, mission support, and good safety procedures can ensure the good proceedings of our EVAs, we wanted to assess how helpful these 3D maps could be to improve performance and lower fatigue. To this end, one test EVA and two sets of experiment EVAs took place, using 3D maps captured from prior EVAs by Crew Journalist Pierre. While the technical results still need to be processed, there’s a strong feeling that 3D maps are a great help for EVA planning.

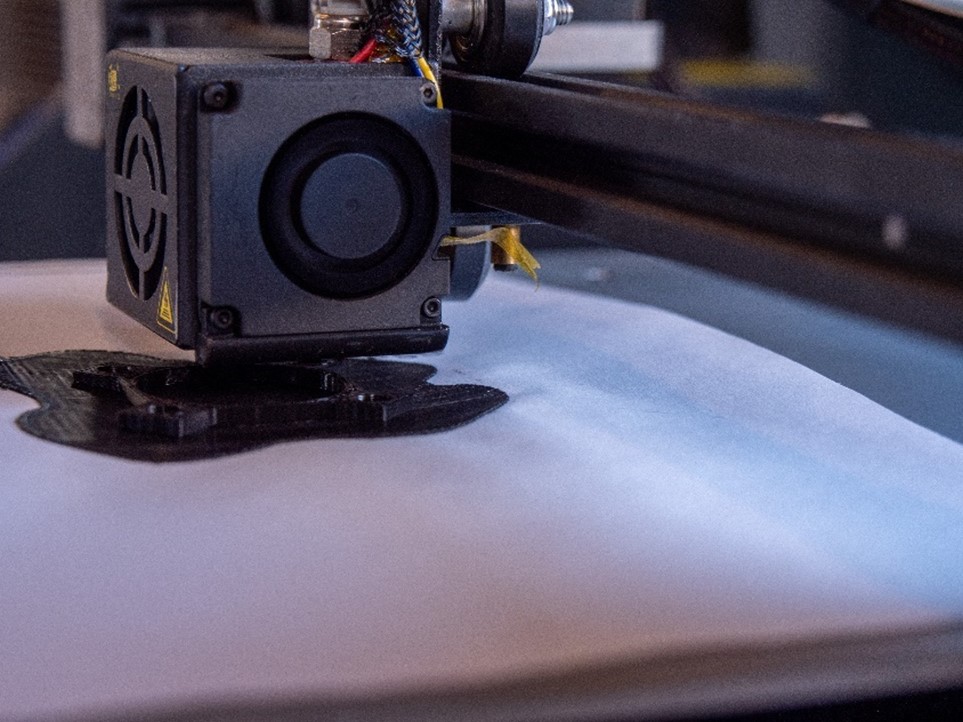

Lastly, a lot of effort was put forward to show the usefulness of 3D printing in situations like this mission, and for future Mars missions, where resources would be scarce, and adaptability was key. In a demonstration that was more focused on outreach and evidencing the vast capacities of these tools, Astronomer Maxime successfully delivered 3D pieces that could technically be created for the repairs to a station or a part of a vehicle, and therefore ensure the integrity of the station.

Biology and Botany

With the originally selected GreenHab Officer’s work being taken over by Crew Scientist Marion, there was still work afoot in the botany area, and experiments focused on biology and general water use were plenty during the mission.

Toopi Organics, a company that – among other works – formulates fertilisers based on sterilised and stabilised human waste such as urine, has entrusted us with a technical test of their products. One part of it was based on sprouting soy in a soil that was based to recreate Martian chemical conditions, to analyse the efficiency of their product. Another application was on the growth of a specific alga called spirulina, which showcases rapid growth as well as good nutritional properties, and could prove in the future to be a valuable source of food for astronauts on Mars. While Crew 222 and 223 had successfully grown spirulina, this experiment aimed to take it a step further by analysing the efficiency of fertilisers on growth. While the sprouting was successful – and a first for city dweller and HSO Julie – errors in the protocols handed to us for spirulina have led to difficulties in growing the algae, and we hope that the following crew will have better luck with corrected protocols.

In the meantime, the Science Dome was busy with two experiments. One of them had been brought to the station for the first time by our own Crew 206, and had been previously tested on the ISS by ESA astronauts: named Aquapad. It consists of a self-contained bacterial culture implement, to easily test for water quality. Beyond the work of Crew Scientist Marion proving that water at MDRS is fully safe, this experiment has proven that astronauts with less formal training could easily assess water quality in a station. In the same domain, water recycling has been an important part of our water management strategy, and the use of frugal processes to clean up water has been successfully attempted by HSO Julie, with shower water being filtered and all solids and dirt being precipitated out of the solution, leading to an increase in available water for improving hygiene and comfort amongst crewmembers.

Astronomy

Astronomy suffered from a bit of a slow start, with many issues unfortunately plaguing both solar and night-time observations, and it sadly took some time for our Astronomer, Maxime, to gain the ability to perform, to some extent, his work of observing the skies. He has been able to perform numerous observations of the Sun, many of which showcasing solar activity, as well as a number of takes for astrophotography. Unfortunately, while many captures were attempted for the research project, which focused on detecting supernovae, the data throughput available to us was deemed too high to fully commit to the experiment, and the results will likely be processed far after the mission.

Outreach

As a student association, our job doesn’t only consist of organising the mission, finding scientific partners and sponsors to be able to get to MDRS. For many years now, a lot of our work has also gone towards building an interest in science and space for schoolchildren of all levels in the region around Toulouse. While this is a year-round job for many people, beyond our MDRS crews, having the chance to perform an analogue mission in a place like MDRS is ideal to create content that can appeal to the students we work with, and we have not missed the chance to do so. Under the creative eye and keen sense of logistics of Executive Officer Marion, a large number of videos, either based on the reports of Journalist Pierre about the experiments we work on, or about the general life in the station were created, and will be the subject of a number of YouTube videos that can be showcased for our students directly, and communicated to the teachers in the schools we are partnered with.

Life in the Station

Supaero crews have always had the chance of working together in close contact for a long period prior to their mission, and of sharing numerous experiences as students, leading to them having strong cohesion and a good understanding on how to live together through the time of Sim. This mission was a little different, since we all had to meet through Zoom and were all in different countries for a big part of the mission prep, meaning that a lot of the traditional cohesion sessions done together in Toulouse were missed by all. Still, with two years to get to know each other and work on the same subjects, we arrived in the USA in high spirits and ready to go on to our mission.

Life in the station was, as much as we could get it, well organised and regulated by our daily exercise, EVAs, the regularly scheduled Human Factors experiments, as well as our personal work. HSO Julie was in charge of our daily exercise, and did a fantastic job of getting some movement out of the half-awake bodies in the Lower Deck at 7:30am. Having been lucky enough to have clear skies and, for the most of the mission, very comfortable outside temperatures, the EVAs were performed in the morning, whether they be focused on drone flights, atmospheric experiments or utilisation of 3D maps, leaving the afternoons open for all the other parts of our daily work routine.

In a rather stereotypical way, good food and nice shared meals were a necessity for this very French crew, and being resourceful with our unusual ingredients was critically important to maintain morale for a group of people where, frequently, a bad meal could be the sign of a bad day. Fortunately, the creativity of every crewmember and the motivation to try to get things to work meant that practically every lunch and dinner were well-enjoyed by all.

Things can be complicated when your workplace and your home are the same, and especially if your days sometimes end at 9pm by the end of the communications window, and occasionally even later, for our very dedicated Journalist Pierre who worked overtime to get our reports done both in English but also in French for our own little communicators in Toulouse. Fortunately, a number of relaxation, meditation or cohesion exercises set up by our HSO Julie have done a great job of allowing us to cool down after our long, tiring days, and brought some very pleasant windows of calm and quiet amid the hubbub of our eternally busy life. The evenings, when we weren’t simply too tired to go to bed, were spent on games and movies, setting up the good mood for the night and to compensate for what was, very often, some very tired mornings.

Three weeks was a long time to spend on a mission – the days were often long, and yet the mission seemed to end surprisingly quickly. There’s been a build-up of fatigue from the long days, a lot of missing our families and the comfort of modern life, and a definite desire to get back to normal life for a good number of us by the end of the assignment. Yet it was a unique moment that held massive value as a human and scientific experience, and one that will stay in our memories for a very long time. In an odd way, we’ll miss life in the station, even though we’re definitely happy to get back to the life we had.

There are almost too many people to thank for this mission and no good order for them. Thanks to all our scientific partners and sponsors, without whom we couldn’t have gone. Thanks to Shannon, Atila, and all the MDRS staff and CapComs who have been crucially helpful throughout our time in the station. Thanks to our friends and families, whom we can’t wait to hear back from. To Crew 263, we bid you good luck, and a great time at MDRS!

-Commander Clément Plagne and the whole of Crew 240

You must be logged in to post a comment.